(If you haven’t read my first blog post about these guys, please start there!!!!)

At the end of my first round of research about Pennell and Atkinson, I had a LOT of questions. The two big ones: Why hadn’t I heard about their relationship before? and did Atkinson feel the same way about Pennell?

The answer to the first one was fairly simple. The small number of people who had read Pennell’s diary in full had, for various reasons which are completely valid, refrained from spotlighting the details publicly. I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to be the first one to do that, and I take it very seriously as an important responsibility.

That leads me to the answer to the second question. Having had some incredibly enlightening and encouraging discussions after the publication of my first post, I decided to pursue further research—well, not decided, really. It felt natural to keep going, to be able to try and draw as vivid and real a picture of them as possible, which meant doing more digging.

The first order of business was to try and track down some of Atkinson’s writings, in order to get his side of the story. This involved accessing the digital archives of the National Library of New Zealand (freely available, like the Canterbury Museum) and the Royal Geographical Society (accessed through my school), followed by an in-person visit to the SPRI archives.

The letters held at the RGS were donated by Pennell’s niece Naomi — credited as his daughter for some reason, but he didn’t have a daughter and the name matches genealogical records for his brother Reginald’s daughter. They include my holy grail — 3 letters from Atkinson to Pennell written at Cape Evans during the winters of 1911 and 1912 — as well as a long letter from Pennell to Atkinson written during the Terra Nova’s voyage home in 1913. In late 1918, shortly before he was wounded on in the explosion of the HMS Glatton, Atkinson forwarded these onto Pennell’s mother-in-law for her to read and choose whether to pass on to Pennell’s widow, Katie.

Separated in the Antarctic

In the first letter dated October 26th, 1911, shortly before setting out on the Southern Journey, Atkinson thanks Pennell for the long letter that he had left with him before the Terra Nova departed in March of that year. The letter “travelled the round at least certain portions of it did and was a great source of enjoyment to all. I had to do this as it was a bit comfortless to the others not having any news to read.”1 Pennell, well liked by all, was greatly missed by more of the shore party than just Atkinson.

“I may not see you but I hope I do as I have a very great deal to say to you, things that one cannot write,” Atch continues. This could quite possibly refer to gossip about Scott’s leadership, seeing as it follows on shortly from Atkinson remarking that “Teddy Evans is a very great failure in everyway conceivable […] unsuited for the job in every way and is very stupid.” Conversely, according to Atch, Birdie, Cherry, Bill, and Titus are “the pick of the whole lot” and Silas is “also a top notcher.”

“Well old dear I am one of the 12 going up the Beardmore and the 8 or 4 fittest at the top will be chosen. Good luck to ‘em,” Atkinson signs off. Two postscripts are attached, one at the top of the first page:

About the second year I have let the Owner know your wishes off my own bat and he told me that “he had been considering it, would like it very much, but that it was a very difficult question.” You would like the life it is good and hard.

And one at the top of the second:

If I don’t see you give my love to every pretty girl you see in New Zealand. ELA

Pennell would have been handed this letter by “Marie” Nelson when the Terra Nova arrived in early January 1912, with all the sledging parties still out. He was looking forward to potentially exchanging billets with Teddy Evans on his arrival, and becoming part of the shore party—as Atkinson had proposed to Scott—and it might well have happened, as Teddy planned to return to New Zealand after his return from the Southern Journey (per the wishes of his wife, according to Pennell). But the dreams of all were dashed when Evans came off the Barrier desperately ill with a bad case of scurvy, and Pennell had no choice but to remain in command of the ship.

Atch stayed onboard the ship caring for poor Teddy for a few days while Pennell led the attempt to relieve Campbell’s Northern Party in Terra Nova Bay, being thwarted by the ice conditions at every turn. But as Pennell wrote to Wilson in a letter included in the RGS materials, with Atkinson on board it wasn’t all bad: “Old Jane has been spinning me all the shore yarns, it is delightful to have him again to talk to, though one could wish him on the Southern Plateau with you people.”2

Eventually the Northern Party were given up for the winter, and Teddy’s condition was deemed stable enough for Atch to return to base, entrusting him to the temporary care of Bernard Day for the journey home.

When Pennell and the Terra Nova left for New Zealand in early March 1912, it was still assumed that the Polar Party would be returning safely by the end of the month before winter set in. There was no reason to believe otherwise. But as April passed and winter set in with no sign of them, it was apparent to all that something had gone very wrong.

The next letters from Atkinson to Pennell are from the beginning and end of that winter, although Pennell wouldn’t receive them until January 1913 when the Terra Nova returned (at which point Atkinson might have delivered them personally).

“As regards the Polar Party I believe they have gone down a crevasse at the bottom or middle of the Beardmore,” Atch tells him in the first of these letters, dated May 9.3 He reassures Pennell that he believes Campbell’s party is safe and that is why he has decided to go south in search of the Polar Party at the start of summer— “This will be openly discussed but that is what will be done.” (This open discussion occurred after Midwinter dinner on June 22, according to Atkinson’s narrative of the second winter in Scott’s Last Expedition.)

During the austral winter of 1912, Pennell was surveying in New Zealand with the ship’s crew, dealing with the mysterious death of stoker Brissenden, and spending time with the Dennistoun family at their home at Peel Forest, trading in his naval uniform for civilian clothes, complete with his characteristic starched stand-up collar—a good few years out of fashion by then. He attended a dinner given in honor of Roald Amundsen at the Kinseys’ home on April 26th, which was also attended by Teddy Evans (by then much recovered but soon to depart for England to convalesce), his wife Hilda, and Oriana Wilson. That must have been an interesting evening.

A few weeks before that dinner, Oriana Wilson had written effusively to Pennell’s mother in Devon:

“I feel I must just write you a little letter to say how splendidly well he looks & how everyone loves to have him in the house, for he is always so cheery & always finds something nice to say about everyone on the Expedition & elsewhere – My husband writes in his journals how dreadfully sorry he is that they couldn’t keep him down South – they think so much of him, but then one can see how indispensable he is on the ship […] What an extraordinary worker and walker he is! full of energy – We all told him he looked so well & had evidently put on weight – he didn’t approve of that at all! & is doing his best to walk it off now[.]”4

In October of 1912, shortly before the Search Party departed, Atkinson wrote the final letter to Pennell included in the RGS collection. He expected the party to be away well into January 1913, aiming to reach the top of the Beardmore in their journey to discover what had happened to the Polar Party.

“You see it really has been a devil of a winter and a very trying time. […] By Jove I shall be very pleased to see you again and shall have a good deal to say,” he writes.5 He ends the letter by telling Pennell: “Mind you try and throw over a few things and we shall get off into the quiet country somewhere away from people after seeing the relations.”

(It doesn’t seem like they were ever able to go off on their own—owing to pressing expedition responsibilities—but a few days in late June of 1913 were indeed spent with Pennell’s relations in Devon, motoring about the beautiful green country, playing tennis, exploring forest glades. That was when Pennell introduced Atkinson to his mother, who “[took] him straight to her heart.”)

Teddy Evans returned to New Zealand, fully recovered from scurvy, in time to take command of the Terra Nova for her final journey to McMurdo Sound in the austral summer of 1912-13. Pennell was deeply frustrated at being superseded in his role as captain, which everyone agreed he excelled at, but he agreed to remain aboard the ship as navigator, serving under Evans’ command. He wrote to his mother before Evans’ arrival: “I have heard from Evans, who evidently implies (though he does not actually say) that he wishes me to stay in the ship; on the whole – in spite of the awkwardness of the position – I am glad of this as it would be very trying to leave before the relief was effected.”6

Pennell must have been especially grateful to have been able to remain aboard when, upon arriving at Cape Evans and hearing the news, the realities of what Atkinson and the rest of the party had endured in the ship’s absence sunk in. He wrote in his diary that “No one can ever know quite how much Atkinson has been through this last winter, magnificently supported by Wright & Cherry.”7

He watched as the members of the shore party, two years gone in the Antarctic, reveled in seeing the seabirds gracefully winging their way about the Terra Nova as it steamed north. But the relief at returning to civilization must have been tempered—for Atkinson and Pennell—by the knowledge that they were the ones who would have to break the news to the loved ones of the Polar Party, and to the world, that the five had perished.

I haven’t been able to find a record of why Pennell and Atkinson specifically were chosen to go ashore with the message at Oamaru. It would have made sense for Evans to do so as he was commander of the expedition entire at that point; Campbell was also aboard and outranked Pennell. If it was expected that Atkinson would go, as he would have to be available to Kinsey and others to answer questions about the relief party in the interval between sending the message and boarding the Terra Nova again at Lyttleton, it may simply have been that Pennell volunteered to go with him.

In New Zealand

After landing at Oamaru and sending the all-important telegram to the Central News agency, Pennell and Atkinson had to make the journey up the coast by train to meet the Terra Nova in Lyttleton harbor, outside of Christchurch. But they couldn’t do it in secret, the same way they had come ashore – reporters had caught the scent of the Terra Nova’s return and were on the trail, dogging them from station to station, a handful of them even boarding the train to continue their inquiries. It must have been an excruciating experience for Pennell and Atkinson, but they kept perfect poker faces—they could not risk giving the game away. Exclusive news of Scott’s expedition ahead of the official release promised to be an absolutely massive scoop, and would surely sell an immense number of papers—unscrupulous behavior is understandable on the part of the reporters, especially given the fact that nobody had any reason to expect that by invading the privacy of the expedition members, they were being disrespectful towards grieving men.

One reporter for the syndicated Press Association happened to be waiting at Christchurch station when Atkinson and Pennell alit from the train. Pennell, having spent a great deal of the past two years in New Zealand, was well-known and well-liked in the area and was recognized by the wily pressman, who at first thought the other man with him was Captain Scott.

“It transpired, however,” the reporter wrote, “that Lieutenant Pennell was accompanied by Dr Atkinson, and that Captain Scott was on board the Terra Nova. By this time Dr Atkinson had entered a taxi-cab, but while Lieutenant Pennell was not disposed to impart the news he held he patiently stood at the door of the taxi in conversation, only to shake his head in reply to each query put by the pressman.”8

Pennell gave a marvelous performance of total secrecy—he shook his head silently in response to question after question, bade the reporter goodbye with a smile, and gave one final polite apology for not being able to tell him anything before getting inside the taxi with Atkinson. They headed to a cafe for some much-needed refreshment before going to Kinsey’s office to start, again, the terrible business of breaking the news.

Pennell defending Atkinson from the voracious press is a theme that crops up repeatedly in newspaper accounts from this period. During an interview conducted on board the Terra Nova, a special correspondent from the Daily Chronicle suggested he might pose questions directly to Dr. Atkinson, and Teddy Evans did not object, except to say that he had a right to limit Atkinson’s answers if the questions put to him were undesirable. But this was not enough for Pennell, who immediately jumped in, playing defense. “I think,” he said, “it would be highly undesirable to enter into details some of which might hurt people’s feelings. And it would be merely pandering to the morbid tastes of a section of the public,” he urged, “to publish things which had better not be published.” Evans, mollified, thus agreed with Pennell that Atkinson ought not to be questioned directly—and so, likely to his great relief, he wasn’t.9

Mere days after the news of Scott’s death was released, sensational statements were published in New York papers which claimed there was bad feeling amongst the crew towards Atkinson for not doing enough to save Scott. In the Lyttleton Times of February 15, Pennell took it upon himself to interrupt an interview being conducted with Evans, in order to dismiss these claims.

“[Pennell] found some difficulty in describing his admiration for Dr Atkinson’s work. He felt very indignant at the statements made in the New York journals. They were utterly untrue. There was nothing to criticise in Dr. Atkinson’s efforts during the relief. There was not the slightest ground for suggesting that criticism of anything Dr Atkinson did came from a single member of the expedition.” Pennell patiently explained to the reporter the dire situation at base camp which had required Atkinson to remain with Evans instead of going out with the dogs to meet Captain Scott.

With Pennell having led the way, other members of the crew including Campbell and Bruce soon entered the conversation in order to defend Atkinson—and Cherry, who had also been suffered injustices at the hands of blameful American editorials.10

The Voyage Home

After the voracious press had been dealt with, members of the expedition dispersed or lingered as their duties demanded. Pennell took over command of the ship again as Teddy dealt with expedition business, getting into various tiffs with Kinsey and Kathleen. The rainy weekend of February 22nd, 1913 found Atkinson and Pennell on a relaxing break at the Dennistouns’ home, Peel Forest, where Pennell had spent so many enjoyable days during the previous winters.

Atkinson departed from New Zealand on March 6, accompanying Oriana Wilson and her sister Constance Souper home on the RMS Remuera, a New Zealand Shipping Co steamer captained by the Kinseys’ good friend Horace Greenstreet (father of Lionel Greenstreet, who would soon join up with Shackleton’s Endurance expedition).

Constance wrote detailed letters home from the voyage to the Kinseys, telling them how Atkinson was an ideal traveling companion—although she admitted she hardly ever spoke to him, since he spent most of his time with her sister, keeping her active and social while on board. “Dr. Atkinson helps her a lot, and insists upon her doing this, that, and the other, sometimes in the most amusing way[.]”11

Atkinson and Oriana made a study of ornithology together, visiting the peaceful stern area of the ship in the mornings, away from the other passengers, to compile a record of the birds they saw each day. As they approached the Horn a diving petrel was blown on board, a “dear, fat, comfortable little thing” which Atkinson brought Oriana so that she could hold.12 They also frequently visited those of the expedition’s dogs which were aboard, being brought back to England as pets—including Captain Scott’s favorite dog Vaida, who Atkinson planned to give to his favorite aunt, the recently widowed Lady Nicholson. In a letter to Kinsey, Captain Greenstreet described a comical scene with Atkinson and the dogs:

How you would enjoy the fun every morning at 6.30 when Dr. Atkinson exercises the dogs. He made a set of harness and a small sledge on teak wood runners, and on this, when the decks are wet, he tears round full tilt, bumping against stations and bolts and occasionally capsizing.13

The charismatic and well-liked Greenstreet was a great friend to the group, and kept them company onboard and ashore during the voyage. He gave Oriana a course in knot-tying and sat across from Atkinson at dinner in the 1st class saloon, ensuring good conversation. Accompanying the group ashore at Rio, he went with them to the top of Corcovado mountain to view the city below; and he spent the day with them at Tenerife, treating them to a fine breakfast and a tram journey through the country.

Oriana wore black mourning clothes aboard the Remuera, so surely their fellow passengers knew at least the broad strokes of what had befallen her, if not the precise details which placed her central to a tragedy that had enthralled the world. But what was also certain was that they could see how much she valued Atkinson’s company, and how untiring and able he was in his efforts to keep her in comfort and good spirits.

Writing to Pennell from the Remuera, Oriana agreed that Atkinson’s help was utterly invaluable to her — and her presence was helping him as well, for it was true that he, too, was grieving. “I have felt so for him,” she said, “but I can’t say it to him – it has been such a relief to see him cheering up and enjoying things.”14

Their bond, strengthened by mutual loss, deepened throughout the voyage. They fought amusingly over money at Montevideo, Atkinson trying to pay Oriana back more than she was owed for the trams and she resisting strongly. In Rio, when they took a drive up into the Tijuca forest, he named all the exotic trees and plants he knew for her.

Constance wrote of Atkinson:

It has been so nice to see him recovering and losing the strain on his face. He was very quiet and rather shy at first, and seldom talked to anyone else on the ship – and I think everyone was a little shy of him – but it is evident everyone has a tremendous liking and respect for him now – and as for the children they simply adore him.

Childrens’ affection for Atch is a theme of these letters: Oriana records too that “they love him dearly – […] and there is one little baby boy who cries when his Mother takes him away from Dr. Atkinson’s arms.”

He gamely took part in the shipboard entertainments, winning first prize for his Robinson Crusoe costume (made by Oriana) at a fancy dress ball near the end of the voyage. According to Constance he had become, by then, “immensely popular, and everyone wanted him for a partner at the sports,” and that “one girl likes him very much, and he is very nice to her – She is a very nice girl.” There were very few who were immune to Atkinson’s charms, once he let them show.

Following behind the voyage of the steamer, the Terra Nova had departed from New Zealand for England via Cape Horn on March 13, taking a lengthy route in order for magnetic, oceanographic, and biological experiments to be conducted in a leisurely fashion. A long letter from Pennell to Atkinson begun in early April and continued throughout the Terra Nova’s homeward voyage, to be sent home from Rio, gives an additional perspective the record of the journey in Pennell’s private diary.

The voyage from Lyttleton to the Horn was a poor show weather-wise, but with Pennell at the helm the ship’s company was in good hands, and he of course enjoyed himself immensely. But difficulties persisted even when the weather improved after they rounded the Horn, thanks to seaman Abbott’s sudden descent into psychosis. Pennell expressed his anxieties in the letter to Atkinson, making all sorts of plans ahead of their arrival at Rio: “If possible [Abbott] will go home by mail steamer from Rio & if so you will see him as soon as you get this. We (Levick & I) are hoping you will be able to meet him, & arrange for his disposal.”15

The Terra Nova’s stop in Rio was recorded in acting British Consul Ernest Hambloch’s unimaginatively titled memoir British Consul. Pennell’s untiring efforts to secure Abbott a comfortable berth on a steamer home from Rio were assisted by Hambloch, who succeeded in getting space made at short notice on the mail steamer Asturias for Abbott and his “inseparable pal” (probably either Heald or Williamson).Hambloch describes Pennell as tall and cheery, and reprints Pennell’s letter of thanks, composed at sea on the way to England:

“ […] We often laugh over our arrival in your office and the bombardment of questions, ranging from where Nelson could get a room to sleep in at once up to how to dispose of Abbott, and including such miscellanies as where to get dog-pills.”

Later in the book Hambloch recounts a chance encounter with Pennell during the war. “Keen, competent, and quietly good-tempered, Pennell was the type of officer that makes the Navy eternal […] No victorious wars can compensate a nation for the loss of its Pennells.”16

Pennell was wholly in his element in command of the Terra Nova, overseeing care of the dogs, the winding of the trawls, the charting of the course. Ever the optimist, he was able to see the good in even the more unsavory elements of the voyage. “As pleasant a yachting trip as can be imagined – the one & only thorn being poor Abbott’s illness, & even this has its redeeming feature in seeing the wonderful gentleness of his nurses & old Toffer [Levick]’s goodness.”

He rarely slept for long, catching a few hours of rest during the daytime in order to oversee night watches, but he still found the time to dream. “You will be amused to hear that the last 2 days I have been dreaming of you,” he wrote to Atkinson. “The day before yesterday I was smashing your bottom with great gusto.”

Entertainingly, Atkinson seemed to find it necessary to explain the above in his short covering letter to Mrs. Hodson, when he sent the packet of letters along after Pennell’s death. “His unfortunate habit of catching me unexpected smacks caused him great delight, hence his allusions.”

(I mean, if you say so!)

Lieutenant “Parney” Rennick had become engaged to a girl in New Zealand, Isobel Paterson, shortly before the Terra Nova departed in 1910, and Pennell observed with amusing detachment his impatience to see her again. “I think nearly all are enjoying [the voyage] […] with the exception of the unfortunate Parney who I believe loathes it, stopping to trawl or swing to him simply means an hour later getting home. Presumably I shall be the same when the world is entirely composed by one fair young thing – at present one simply marvels.”

Though mere months later in his diary he would record with absolute honesty the distress he felt at missing Atkinson, at sea it seemed he had a different perspective. “This little absence has given a very keen edge to the pleasure of looking forward to seeing you again. If the navy means everlasting break ups & paying offs it also means a great many meetings again & these are the pleasures of life.”

He adds a postscript to the letter: “Excuse length, writing & spelling. Writing to you like talking one becomes rather verbose.”

Before and During the War

Atkinson escorted Pennell’s sisters to Cardiff to meet the Terra Nova in June 1913; this was followed by the short and happy interlude in Devon with Pennell’s family. After that, Pennell and Atkinson settled into post-expedition work and life in London. Dealing with the internecine politics of the expedition committee was stressful, and the business of sorting out scientific results complicated—but they managed keep up an active social life as the prewar summer idyll of 1913 ripened.

Along with a few others, they shared a home at 15 Queen Anne St, Cavendish Square, which must have been a whirlwind of activity. Writing to Davies, the carpenter of the Terra Nova, in mid-July, Atkinson remarked that he was “[h]aving a lot of trouble with Mr. Pennell he will insist on getting up at 6.30.”17 Pennell wrote to Davies around the same time, telling him that “Dr. Atkinson is here & wishes to be remembered to you.”18

The latter half of 1913 was, as mainly gleaned from Pennell’s diary, filled with an enormous amount of work as well as leisure. Spending weekends traveling—to Cambridge, Oddington, Lamer, or Awliscombe—and weeks in town, working on expedition reports by day and enjoying the charms of London’s theatre and restaurant districts by night, often accompanied by Atkinson, and sometimes Lillie, Davies, Rennick, or their roommate/landlord Jimmy Wyatt.

Before Atkinson departed for a holiday visiting family in the West Indies, he and Pennell discussed the possibility of going on another expedition—what might they discover together?

Atkinson was absent from August 13 to September 15. Pennell eagerly counted the days until his return, and picked him up at the station. It was then that he (Pennell) revealed, to his diary and posterity, Atkinson’s involvement with his wife-to-be, an actress in Exeter—the “redheaded and vivacious” Jessie Ferguson.19

Aside from this, and Pennell’s subsequent surprise engagement to Katie Hodson, they continued to happily share a household, referring to each other often in letters. Writing to Cherry in October of 1913 Atkinson noted that “Penelope had a tummy ache last night he looked absolutely ghastly.”20 Luckily their house was on a block off Harley Street and they were surrounded by doctors, including Jimmy Wyatt, so hopefully Pennell’s discomfort was not long lasting.

The following month Pennell informed Mrs. Kinsey that “Atkinson and I have a little Xmas present for you & Mr. Kinsey but unfortunately it will I am afraid be a little late.” He reassured her that all was well with them: “Dr. Atkinson with his wrinkles out of his forehead and the crows feet away from the corner of his eyes.”21

Soon after that Pennell wrote to Davies, thanking him for congratulations on his engagement: “So you see I am not the confirmed bachelor you used to fear I was.”22 And in early 1914 Atkinson invited Cherry down to their house to say a farewell to Pennell before he departed for Switzerland to meet the Hodsons.23

Pennell was informed of a forthcoming posting as navigator to the HMS Duke of Edinburgh at the beginning of 1914, and soon afterwards Atkinson departed for China to investigate parasites with Robert Leiper, accompanied by Cherry. The happy household at the Wyatt’s was broken up by March.

Their lives were headed off in different directions well before the war, thanks to marriage in the offing for both of them, to say nothing of the vicissitudes of Naval postings. And the war would naturally prove even more of a separator.

Though no letters to each other from the post-expedition/wartime period have survived, they certainly wrote frequently. In May of 1914 Pennell wrote to Silas Wright to give him an updated address for Atkinson in China, different to the one he left behind when sailing,24 and Atkinson in a letter to Cherry in 1915 told him that “Penelope writes very cheerfully but unfortunately I have missed him as his squadron and ours have now changed billets and so I may not see him again before I go over.”25

They met at least a few times on duty in late 1914. “The illustrious Pennell turned up the other day, and I was alongside in the skiff as soon as she dropped anchor. He really is an old dear blessed with all the virtues and I would give anything to be with him. I have only seen him once since then as we are on different duties and are seldom in together,” he wrote to Mrs. Kinsey.26 In April 1915, Pennell married Katie Hodson in Oddington, in a ceremony officiated by Katie’s father, rector of the parish. Like many weddings during the war it was on short notice, Pennell only having leave from his ship for a few days, and so not everyone invited was able to attend. A long newspaper account of the wedding reported: “In the absence of two personal friends of the bridegroom, Fleet Surgeon E. L. Atkinson and Mr. D. G. Lillie, M.A. (both of whom had been with him on Capt. Scott’s Antarctic Expedition), the Rev. C. B. Hodson [Katie’s brother] also acted as best man.”26.5

But Pennell and Atkinson did manage to meet at least once in the first half of 1916. Atkinson recounted to Cherry in March of that year: “I saw Penelope on his way through and his Missus she is nice and pretty.”27 This was probably the last time they saw each other.

For a comprehensive account of Pennell and Atch’s movements during the war leading up to Pennell’s death, including accounts of both of their marriages, I highly recommend Anne Strathie’s From Ice Floes To Battlefields. It is an incredibly researched and engrossing read, with lots of further details certain to interest anyone who has gotten this far in this post ?

In late May of 1916 Atkinson confessed to Cherry that, unable to refuse, he had accepted leadership of the shore party of the Shackleton relief expedition, under overall command John King Davis in the Discovery.28 It wasn’t what he wanted—he preferred battlefield action, and the punishing duties of the Western Front over nearly anything else—but perhaps this was a chance for him and Pennell to return to the Antarctic, like they had idly discussed during those summer days before the war.

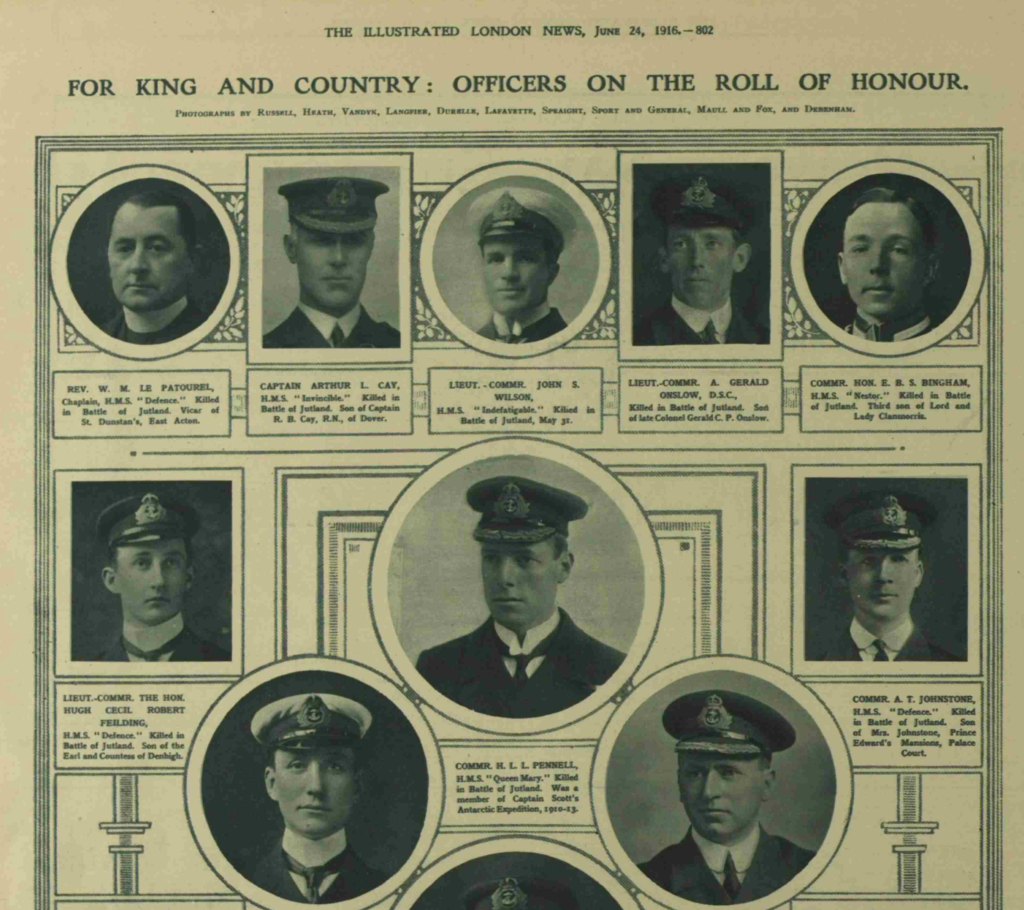

And then a curious twist of time. The Battle of Jutland occurred concurrently with the arrival of Shackleton at the Falkland Islands. The world learned, as soon as the telegram reached England, what had happened to the Boss and his men. Atkinson would have seen with relief that Shackleton was safe, and that his services would no longer be needed, on June 1 or 2, 1916. Pennell was already dead by then, but he would not have known, until the loss of the Queen Mary at Jutland was reported on June 3. Hope, perhaps, still—until Pennell’s name was published in the list of losses on June 5.29

A quiet and private man, never in letters nearly as intimate and honest as Pennell often was in the privacy of his diary, Atkinson’s powerful grief at Pennell’s loss nevertheless is apparent in his correspondence from after the Battle of Jutland.

To “Chippie” Davies, Atkinson wrote: “The Committee had offered me the command of the Land Party for Shackleton’s relief and I had asked for Captain Pennell for the ship I wish to God now it had come off and he had been out of Queen Mary. He wrote to me about you also and I wanted you to come and would have tried very hard for you. I know he was a good friend to you and I feel his loss very much.”30

To Mrs. Kinsey:

I am afraid that you already will have seen the loss of our very great friend Pennell in Queen Mary and you will know how very sore I feel about it all. His little wife is splendid but it has been a heavier loss [even] for her and I feel for her very deeply. Fate in these cases seems so hard and so very inexplicable. I would willingly have taken his place.31

To her as well he expressed regret at not being able to get Pennell off his ship in time to sail with Shackleton’s relief. It is quite true that Atkinson was very grateful to not have to leave his post at the front for the voyage after all—he told Cherry as much—but at the same time if he had tried a little harder, perhaps, acted more enthusiastic about the prospect of going South together, might he have gotten Pennell off his ship just in time for him to be saved?

Everyone knew that Pennell and Atkinson had been close—at least everyone who counted, those friends who, after Jutland, wrote to Atkinson directly with notes of condolence.32 Some may have been addressed to the Wyatts’ home at 15 Queen Anne St, Cavendish Square, where he continued to receive mail. The memories those rooms held were even more precious now.

In 1916 some months after Pennell’s death, Atkinson made time during a short period of leave from active duty at the front to see Pennell’s sister Winifred, and most likely his widow Katie too.33 It may have been at this time that he was given the packet of private letters that now reside at the RGS, for Pennell had written on their covering:

Awliscombe

Feb 1914

In case of my death please seal these up

& send them to Surgeon E. L. Atkinson R.N.

if he survives me.

Conclusion

In the lobby of the Scott Polar Research Institute, below the beautifully painted ceiling, an Adelie egg is on display. Collected by Atkinson and given as a gift to his sister Hazell, the display records it as having been blown by Pennell. Perhaps he did it aboard the Terra Nova or in New Zealand at some point in 1912, after the disappointment of not being able to swap into the shore party had passed off and he was back to reveling in the freedom of his first command. Carefully blowing the egg, he might have reminisced happily about the few days Atkinson had spent on board. Stressful days—Teddy near death, Campbell still stranded—but ones to be thankful for all the same, for the simple pleasure of Jane’s company, which always brightened any hour.

A QR code next to the egg labeled “Sexual speculation over a speckled specimen” leads to an audio clip about Murray Levick’s studies of homosexuality in penguins, recorded by a guide who leads LGBT+ tours at the museum. Interesting, of course—I enjoy the tale of Levick’s miscreant Adelies as much as anyone—but I wondered if there might be room there, if nowhere else, for a nod to the romantic friendship betwen Pennell and Atkinson, as LGBT+ representation in the form of the actual expedition members associated with the object on display.

After all of this research, my original question of “was the feeling mutual” seems rather surface-level. But certainly they loved each other—that much I can’t doubt at this point.

Atkinson was an expert in parasite taxonomy; he named many an “enchanting little ‘pawasite’”34 after members of the expedition and associates. Harry Pennell was immortalized as Macvicaria pennelli, a fluke found inside the emerald notothen fish native to the Southern Ocean. Though that name has survived, Nobel Prize-winning helminthologist William C. Campbell noted that many of Atkinson’s species names are now “of doubtful validity” and have since been superseded.35 Indeed, the name they gave to themselves and their relationship probably would not belong to the same taxa as the one we assign it over a century hence.

But to look at it, carefully, a little awed, under a microscope and do our best to describe its delicate parts—that is something I think they both might understand.

Endnotes

1. Atkinson to Pennell, 26 Oct 1911, Royal Geographical Society MS HLP/2/2

2. Pennell to Wilson, 6 Feb 1912, RGS HLP/2/5

3. Atkinson to Pennell, 9 May 1912, RGS HLP/2/3

4. Oriana Wilson to Mrs. Pennell, 7 April 1912, Mortlake Collection of English Life and Letters, 1591-1963, Accession 1969-0024R, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Special Collections Library, University Libraries,

5. Atkinson to Pennell, 26 Oct 1912, RGS HLP/2/4

6. Pennell to Mrs. Pennell, 8 September 1912, Mortlake Collection of English Life and Letters, 1591-1963, Accession 1969-0024R, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University

7. This & all subsequent quotes from Pennell’s diary are from Canterbury Museum MS433.

8. New Zealand Herald, 11 February 1913, page 8 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19130211.2.85.1?items_per_page=10&page=2&query=pennell+atkinson&snippet=true

9. Western Mail, 14 February 1913 https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000104/19130214/110/0005

10. Lyttleton Times, 15 February 1913 https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0003346/19130215/186/0012?browse=true

11. Constance Souper to the Kinseys, Alexander Turnbull Library, MS/0022/44

12. Oriana Wilson to the Kinseys, Alexander Turnbull Library MS/0022/43

13. Horace Greenstreet to Mr. Kinsey, 7 Apr 1913, Alexander Turnbull Library MS/0022/41

14. Oriana Wilson to Pennell, Mar 1913, Royal Geographical Society HLP/2/19

15. Pennell to Atkinson, 6 Apr 1913, Royal Geographical Society HLP/2/5

16. Hambloch, British Consul: Memories of Thirty Years’ Service in Europe and Brazil, 1938

17. Atkinson to Davies, 19 Jul 1913, Canterbury Museum, Acc. No. 2023.4.10

18. Pennell to Davies, 6[?] Jul 1913, auctioned by Bearnes & Littlewood https://www.the-saleroom.com/en-gb/auction-catalogues/bearneshamptonandlittlewood/catalogue-id-bearne10101/lot-99606dc8-0b6c-41da-8e24-ada900a01011

19. Adrienne Reynolds, Forest School 1834-1984, Forest School

20. Atkinson to Cherry-Garrard, 8 Oct 1913, SPRI MS559/24/8

21. Pennell to Mrs. Kinsey, 9 Nov 1913, Alexander Turnbull Library, MS/0022/46

22. Pennell to Davies, Dec 31 1913, reproduced in With Scott Before The Mast, Reardon Publishing, 2020

23. Atkinson to Cherry-Garrard, 4 Jan 1914, SPRI MS559/24/9

24. Pennell to Wright, 7 May 1914, auctioned by Charles Leski Auctions

25. Atkinson to Cherry-Garrard, 19 Jun 1915, SPRI MS559/24/16

26. Atkinson to Mrs. Kinsey, 27 Dec 1914, Alexander Turnbull Library MS/0022/41

26.5. Gloucestershire Echo, 14 April 1915 https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000320/19150414/075/0005

27. Atkinson to Cherry-Garrard, 8 Mar 1916, SPRI MS559/24/27

28. Atkinson to Cherry-Garrard, 25 May 1916, SPRI MS559/24/30

29. Anne Strathie, From Ice Floes To Battlefields, The History Press, 2015

30. Atkinson to Davies, 19 Jun 1916, Canterbury Museum, Acc. 2023.4.20.

31. Atkinson to Mrs. Kinsey, 22 July 1916, Alexander Turnbull Library, MS/0022/41

32. Atkinson to Cherry-Garrard, 12 June 1916, SPRI MS559/24/32

33. Katie Pennell & Winifred Pennell to Davies, July 28 & Dec 26 1916, reproduced in With Scott Before The Mast, Reardon Publishing, 2020

34. Atkinson to Cherry-Garrard, 4 January 1914, MS559/24/9

35. Campbell, W. C. (1991). Edward Leicester Atkinson: Physician, Parasitologist, and Adventurer. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 46(2), 219–240.

Massive thank you to the Penelopatchicus Antarctica transcription crew once again — Sarah, Becca, Madeline, Jess, Anna, Han, Branwell, Emma, Eva, Kt, R, & Anna. Thanks as well to Naomi Boneham at SPRI for permission to publish quotes, Adele Jackson at the Canterbury Museum for assistance and permission, Sarah Airriess & Anne Strathie for incredibly helpful and inspiring correspondence, Hattie for the Pennell pilgrimage, and especially to everyone whresponded so encouragingly to the first blog. Pennatch 4evs!

Leave a Reply