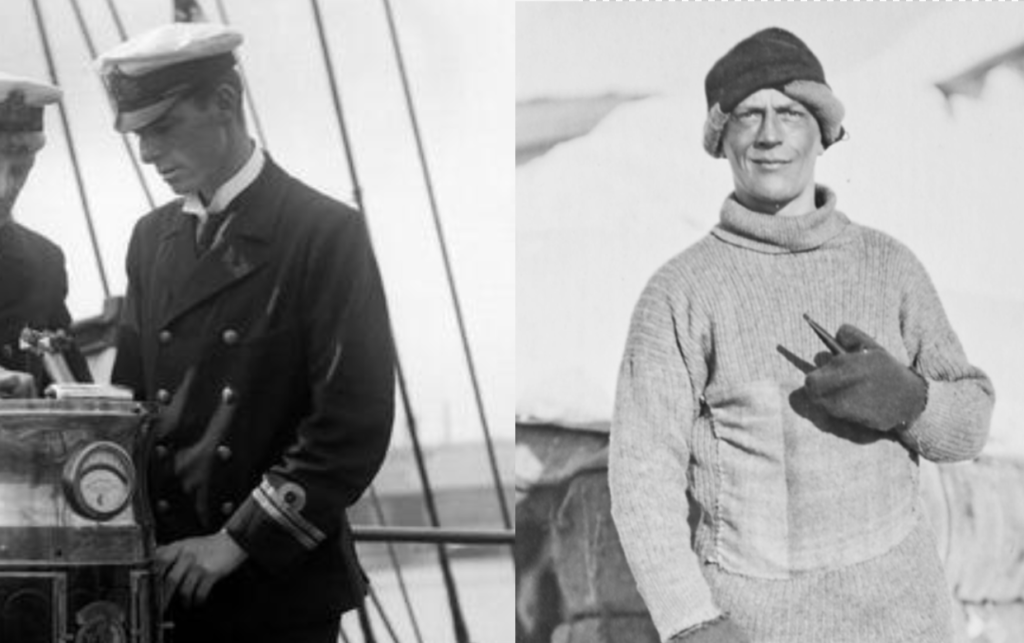

Harry Lewin Lee Pennell (1882-1916) is perhaps the most unsung member of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition. Responsible for commanding the ship during the time the shore party was stationed in Antarctica, he was in charge of repairing the vessel and surveying in New Zealand during the winters, and venturing out to resupply the expedition in the spring.

Sarah Airriess, creator of the Worst Journey graphic novel, has a wonderful intro post about Pennell here, which is where I first learned about him—that he was “suspected of being in Love” by Charles “Silas” Wright, and that his intelligence and diligence impressed Henry “Birdie” Bowers. As recorded briefly in Sara Wheeler’s excellent biography of Apsley Cherry-Garrard, Pennell spent some time with Cherry after the expedition, and Cherry was among the ones grieving the most when Pennell went down with his ship in 1916 during the Battle of Jutland.

Not knowing much more than this, I thought Pennell was handsome and interesting, and so after a leisurely Sunday reading a copy of Frank “Deb” Debenham’s published diaries at the New York Public Library, when I wasn’t quite ready to leave the Terra Nova boys behind, I was delighted to find that the Canterbury Museum of New Zealand had made freely available a PDF scan of Pennell’s private diary covering his years on the expedition.

I was looking for information about my other favorite members of the expedition, the scientists Debenham, Wright, and Taylor, but I knew I would be happy to find any sort of century-old “tea” of the kind I’d come across in Deb’s diaries (such as his comical dislike of his bunkmate Tryggve Gran).

Little did I expect I would come across across a love story.

The Expedition Proper

Pennell’s diary, marked “PRIVATE” on the cover, opens in summer 1909. Having just taken his exam in Nautical Astronomy, he was assigned to the HMS Cambrian in August of that year, and around that time he “had the cheek” to apply to the Terra Nova expedition, still at that time referred to as the “Scott Evans Antarctic Expedition.” The next we hear of the expedition Pennell is, after some long, boring months on the Australian station, bound back to England from Hobart in April 1910 to join up with the Terra Nova.

June of 1910 was a whirlwind, with Pennell immediately becoming involved in the administrative and organizational aspects of the expedition. By the time the Terra Nova departed Cardiff on June 15th, Pennell was at home in his position as lieutenant-navigator, ranked under Scott, Evans, and Campbell. The wardroom at that point included zoologist Wilson, physicist Wright, meteorologist Simpson, and (as recorded by Pennell) “bacteriologist” Atkinson. Pennell felt a little outclassed: “It is most extraordinarily interesting to listen to the talk in the mess as everyone is more or less an expert in some line […] I must say I often feel rather a worm & appallingly ignorant.”

In July, at sea, the work-loving Pennell was utterly content. “One is so perfectly at peace here that I really would not mind how long it lasted, the Meteorological log, Current Book, Magnetic Observations, and Zoological Log taking up every bit of time not already occupied by ships duties.”

He recorded his impressions of many of his messmates as well as the men. The first time he discussed Atkinson, it was from the perspective of the ship’s company as a whole:

“After Wilson, Atkinson is the favourite and that is natural, for he is an out and out gentleman with the quiet self assurance that makes a man without making him offensive. Now Wilson is gone, Atkinson gets the hearing of all our troubles, and he lends a very sympathetic ear. His worst point I have seen at present is that he will, not exactly dislike, but not-like a particular person on very short acquaintances and for very insufficient grounds, I think, very often.”

But by the time they arrived in Melbourne in October, his bond with Atkinson seemed to have grown more personal and intimate. After a dinner at the university, Pennell went back to the hotel, and “finding Atkinson turned in had a long yarn with him about the ship. I have great faith in his judgement in many matters and, whether I agree or not, find his point of view worth considering, particularly as he is very much in touch with the mess deck feeling. At any rate it’s a good thing I think to have someone with whom I can discuss matters without reserve & is safe to keep them quite quiet.”

As the expedition departed their last port, Lyttleton, for Antarctica, Pennell was—so I thought—reaching a fever pitch of personal honesty about his regard for Atkinson.

“It is extraordinary how fond I have become of Atkinson, who is a very fine type of man with high ideals of a very sympathetic nature. The defects of his qualities come out in rather an undue amount of obstinacy. The extraordinary thing about the man is that he will let himself get tight [drunk], when pressed to drink like on the last few days at Lyttelton and he is too good a chap for it to be funny.”

And a few days later, when the ship is held up in the pack:

“I have seen a good deal of Atkinson in spite of the large numbers onboard. He is a most attractive individual & intensely human, & although disagreeing with him on large number of points, yet his view has always a very sound side to it.”

I admit, I was a bit fluttery about all this. What a delightful relationship, which I had never heard reference to in all my research! I wondered, at this point, how it would develop, when Pennell was on the ship and Atkinson was on shore in Antarctica.

Pretty much all of the officers of the expedition had nicknames that they were most commonly referred to by—Cherry-Garrard being “Cherry,” Henry Bowers being “Birdie,” etc. I’ve seen Atkinson referred to most frequently as “Atch,” but around December Pennell (who was known universally as “Penelope”) began to call him “Jane” in his diary entries. When the ship landed the party at Cape Evans in January 1911, Pennell remarked how “[it] was rather a jar saying good-bye, particularly to Jane who poor chap was snow blind already.”

I thought this would be the last we’d hear of Jane until the ship arrived again in 1912, but in Pennell’s next entry dated April 14 (months after he’d last seen Atkinson) he took the time to record an anecdote from when the expedition was in New Zealand, and some officers including Pennell and Atkinson were having dinner with George Wyatt (the expedition’s London agent) and his wife. After Pennell left, Atkinson (who had been drinking) got a little frisky with Mrs. Wyatt:

“Mrs. Wyatt was then singing & she has a wonderfully nice voice, which I like more than any other woman’s I have ever heard. Jane did himself well & apparently afterwards sang himself & they danced a bit. When seeing him off to the train he put his arm around Mrs. Wyatt’s waist and told her she was the most beautiful woman in the world. Mrs. W. when asked afterwards what she thought about it said “Well if George couldn’t see that another man’s arm was around his wife’s waist while he was walking due behind I don’t see why I should object.” Apparently the yarn finished by her saying ‘I simply love Aitch.’“

In the same entry, Pennell discussed spending time in New Zealand with the ship’s party’s biologist, Dennis Lillie, and how the conversation reliably turned to Atkinson: “One thinks a lot about the party down South. It is difficult to realise how one likes ones messmates till they are out of reach. Lillie & I cannot be together more than an hour without talking about Jane, as the real link between Boughey & myself is little Gerry so that between Lillie & I seems to be Jane with his obstinate nature & very lovable character & his curious code of wanting to be able to drink as much as anyone else.”

Boughey and Gerry were two of Pennell’s friends from the Navy, Alfred Fletcher Coplestone-Boughey and Gerald Lord Hodson. They met as sub-lieutenants on the Mercury in 1904. Pennell would end up marrying Hodson’s sister Katie in 1915, but long before that, in May 1908, he had written about Gerry (in an earlier diary also scanned and uploaded by the Canterbury Museum):

“The Forest was perfection and I can say no more; and so was Gerry for I’ve never loved him more. He is so keenly alive to beauty, and so absolutely straight. He can no more lie than a fish can live out of water. Ambition and obstinacy tempered by an appreciation of his limitations which he must & will overcome will carry him through and whether he fails or succeeds in the world the world will be the better for his having lived.”

And only a few months later:

“Gerry supposed[ly] yearning for my company, complimentary! But hardly satisfactory in the navy when it is always parting. Till I met him I thought I should never know what real love was, and now he could twist me round his little finger.”

I’m far from an expert in Edwardian sexuality, and have no idea how Pennell would describe himself or his orientation if he lived today. But he was a conservative, pious military officer who nevertheless took the time to record romantic feelings towards more than one man (as we will see) in his journal, amidst a conspicuous absence of anything remotely similar regarding women in his life. With regards to another Navy friend, he described his affection for him thusly in 1905: “[He] has always attracted me wonderfully but then the attachment is rather a one-sided arrangement – and it is right, it should be.”

(Lillie, it must also be noted, is the one member of the Terra Nova expedition for whom evidence of probable queerness has been publicly mooted thus far, as detailed in a #PolarPride Twitter thread by Sarah Airriess.)

In March 1912, when Pennell took the Terra Nova out to resupply the expedition for their second year, and to pick up some of the shore party members who would not be staying, he was shocked to find Teddy Evans deathly ill with scurvy after returning from the Southern Journey. He was expecting to have been approved to join the shore party and have Evans take over his role on the ship, but with Evans’ incapacitation, as well as ice conditions preventing Lt. Campbell from being picked up from Evans Cove, that was impossible. He would have to remain in command of the ship for another season, to his chagrin, as “a year with Jane & Bill etc would indeed have been bliss.” But for the little while that Atkinson was on the Terra Nova taking care of Evans before being landed again, “It was a great pleasure to have him onboard & as he had little to do I saw a great deal of him. The idea of landing and being with him & the others for the winter added to the sledging was so attractive that the miscarriage of the scheme at the last moment was most annoying.”

At this point in my reading it was undeniable that Pennell’s feelings about Atkinson were really something special, and I wondered why I’d never seen the relationship remarked on in any of the copious amounts of nonfiction about the expedition I’ve consumed—apart from saying that Pennell was well-liked and members of the expedition were saddened at his death.

Okay, maybe Pennell wasn’t “important” in the way that Atkinson (discoverer of the Polar Party’s remains and leader of the expedition during that final year) was, but surely the insight of how particularly and deeply Atkinson was beloved by the ship’s navigator was worthy of reporting?

The austral winter and autumn of 1912 were spent in New Zealand, surveying on behalf of the government, the enjoyment of which for Pennell was only interrupted by the news that Evans, recovered from scurvy, would be rejoining the ship and taking command in time for the next journey out to Antarctica to (presumably) pick up Scott. This was a disappointment to Pennell, who at first assumed it would mean he would have to leave the ship entirely. However later it was determined he would merely take the subordinate (“almost humiliating”) position of navigator. Also during this time a popular member of the crew, Brissenden, was found drowned under mysterious circumstances, which cast a pall over the ship and over Pennell as he had to take part in the subsequent inquest. But the spring was enjoyable enough, full of birdsong and tennis and leisurely camping expeditions in the countryside.

On December 14, the Terra Nova, “laden with plum duffs” and under command of Evans, set off for Antarctica for the final time.

And on January 23rd, 1913, Pennell opened his entry covering the previous six weeks with the line: “To strive, to seek, to find and not to yield.”

Precisely one year after Scott and the Polar Party reached the pole, Pennell & the ship’s crew had been informed on January 18th of their fate. “Jane has had a very bad winter, but has risen to the occasion and kept his party in spirits under the most trying circumstances,” Pennell wrote. He was also very impressed with how Campbell led his Northern Party through a hellish winter stranded on Inexpressible Island. Reflecting on the effects of leadership, Pennell remarked: “Campbells wrinkles are coming out of his face fast and now he looks younger than when he first joined the ship in London. Jane is much more marked–lines all over his face, which now, in repose, has a thoughtful almost sad look. The expedition will I think affect him more (permanently) than any other member.”

Returning To New Zealand

One thing that Pennell has actually been widely acknowledged for is his role in delivering the news of Scott’s death to the world. The town of Oamaru celebrated the centenary of this event in 2013, even going so far as to reenact the journey of Tom Crean rowing Pennell and Atkinson to shore under cover of night on February 10, 1913.

After Pennell and Atkinson came ashore, they spent the night on the floor of the home of Ramsay, the harbormaster. First thing in the morning, they sent a brief cable to the expedition agent Kinsey in Christchurch, and then “went & sat in a field” together while waiting for the 11am express train to Christchurch. On the train they fought off reporters who were angling to find out the news before anyone else; in Christchurch Pennell accompanied Atkinson to the Kinseys where Mrs. Wilson was waiting, and watched him break the news to her (though she had already found out on the train down from Dunedin); they slept that night at a hotel in Sumner and then in the morning walked out to meet the ship.

The next week was spent preparing lengthy dispatches and writing letters. Pennell and Atkinson stayed together at the Kinseys’ house at Te Hau: “Mrs. K carefully arranged that J & I should sleep together in the Cabin & apologised very much for having to put us in the one room.” Pennell and Atkinson went on a weekend jaunt to Peel Forest to visit the Dennistoun family, whom Pennell had befriended during his winters in New Zealand, and then again spent time together with the Kinseys, Mrs. Wilson and her sister at Te Hau. Pennell and Atkinson were asked to be godfathers of a baby (of Dr. Hugh Acland and his wife, whom Pennell had also befriended during the NZ winters), and with Lillie they were offered a bedroom available to stay in at the Aclands’ whenever they wanted to during the month of February.

Atkinson departed New Zealand on March 6th, escorting Mrs. Wilson and her sister back to England, and Pennell went to see them off from Wellington, staying with Atkinson at the Royal Oak (“the best hotel in Wellington but such a dirty place”).

Remarking on the past month since arriving in New Zealand, he mused that “In some ways this has been a very happy month. None could have imagined how nice everyone could be until this sort of thing occurred, the thoughtfulness & sympathy of all our neighbours, the press & the public has been wonderful,” adding on a separate line: “Then the whole time has been practically with Jane & this need not be emphasised.”

Back To England

Pennell was in command of Terra Nova on her journey back to England, the head of a reduced mess that included (of the original expedition members) Lt. Henry “Parny” Rennick, Dr. Murray Levick, Dennis Lillie, carpenter Francis Davies, and biologist Edward Nelson stepping into a position as 2nd mate. They also had 13 dogs onboard, survivors of the Antarctic trip.

They took the Cape Horn route, stopping at Rio and the Azores on their leisurely way back to England. Pennell paid close attention to all of the birds and marine life spotted on the voyage, and took some water samples for Silas Wright to analyze for radium content in Cambridge. On March 17, 1913, Pennell noted mournfully, “The sunset tonight was very beautiful. How these lights at sea bring Bill back to memory, it was one of the subdued-lights nights that he appreciated so much.”

The main event on this voyage was the unfortunate condition of P.O. George Abbott, who had been a member of Campbell’s Northern Party. In mid-March he was struck with a severe episode of delusional psychosis which saw him having to be held down on the wardroom table when he grew violent, and watched over round the clock by Dr. Levick and the crew for days at a time. Luckily Pennell and Levick were able to get Abbott a room in a hospital when they reached Rio, and entrusted him to the care of a friend to see him safely back to England.

On this voyage, Pennell read at least one book given to him by Atkinson (“The White Slave Market” by Mackirdy and Willis) and was given a caricature of Atkinson by Lillie, who was an accomplished cartoonist: “Lillie has given me a caricature of Jane done yesterday. It is wonderful how he keeps different persons’ peculiarities in his head.”

It’s not known which of Lillie’s drawings this was—but there is in fact at least one extant drawing of Pennell and Atkinson together during the expedition by Lillie. Titled “Antarctic Lovebirds,” the drawing depicts avian versions of the two in a tree as the rare species Penelopatchicus antarcticus, performing what seems to be some kind of mating dance:

London

At this point in my reading, I was wondering when or if Pennell would meet Atkinson in England. I imagined that surely they’d see each other again, even if just on post-expedition business—but I really had no idea what I was about to encounter in this next section.

After arriving in England in June, Pennell’s entry dated July 6, 1913 records the events of the month prior. The Terra Nova docked in Cardiff where Pennell’s three sisters came to meet him. He attended some official functions and visited local sights with his sisters, eventually turning over the ship for the final time to Evans on Monday, June 23rd, and then taking the train directly to his family home in Awliscombe, Devon.

There he met his mother and sister, and attended church with them—and then he met Atkinson, who had already arrived that past Saturday to stay with the family.

Atkinson and Pennell spent the week leisurely in the area, playing tennis, seeing friends, and motoring about the countryside, often with Pennell’s sister Dorothy. And when Atkinson finally left on that Friday, Pennell recorded:

“Atkinson had to leave on Friday. Mother has taken him straight to her heart, as I knew she would. I am quite absurdly in love with him & look forward to seeing him again, if only a day or two parted, with quite amazing keenness.”

He said it!

Wow!!!!!!

But wait, there’s more…

In London, Pennell moved into new rented rooms at 15 Queen Anne Street, lodgings which he shared with Atkinson (!) as well as a few other acquaintances. With his usual love of work, he embarked on the ceaseless, complex business of winding up the expedition, completing important map and magnetic duties. He visited Cambridge with Atkinson to arrange for Lillie’s specimens to be examined there, accompanied Atkinson to visit Scott’s mother, and attended meetings of the Expedition Committee, which thanks to the intransigency of Teddy Evans was facing difficulties.

On weekends he sometimes took the train out to visit his family in Devon. In the evenings, he could be found frequently dining out and attending theater in town: he had a love for food and entertainment. Atkinson was very often in attendance socially with Pennell, as occasionally were Pennell’s sisters when they were in town. On August 6th he recorded: “Theaters up to date have been ‘Beauty pulls the strings’, ‘General John Regan’; ‘The Milestones’ and ‘The Great Adventure.’ Jane took me to them or else came as well & they were all most enjoyable. The Great Adventure was the best acted, in fact it could not have been better, but all were absolutely first class.”

On July 26th, at a special ceremony, Pennell wrote that “the King presented us with the medals. Crean & Lashly with the Albert Medal 2nd class in addition. The King told Jane he had done very well, a kindly & well deserved acknowledgment of the way he has behaved.”

Atkinson also took Pennell to meet his own sisters who lived in Portman Square: they would all of them be departing in August for the West Indies, where Atkinson had been born, for a holiday to visit family. Pennell went all the way down to Southampton with them to see them off when they sailed, and then returned to his bustling life in London.

He still had an immense amount of work, as well as constant social engagements in the city and elsewhere, but it seems he could not get his mind off one particular subject. Near the end of the entry dated August 22, 1913, he wrote:

“Find myself counting the days till Jane returns, it is almost aggravating at times to be so violently in love with a man. It is lucky to have so many months with him now.”

Gerry Hodson, his old Navy friend (and possibly first love) was home on leave, so Pennell visited the Hodson family’s home village of Oddington during this time, and entertained Gerry and his sister Katie in London as well.

In early September Pennell visited Lamer, the Hertfordshire estate of Apsley Cherry-Garrard, and enjoyed a weekend of shooting, ahead of a planned trip with Cherry and Atkinson up to Atkinson’s aunt’s estate in Banff, Scotland. At the end of the weekend Cherry drove Pennell back into London, where he would meet Atkinson back from the West Indies, before they both went up to Scotland together.

This meeting occurred—but was tinged with sadness.

“Jane was very bright & happy when he arrived & fled off to Essex where his lady love lives – but that is another story.”

Another story which does not, as it were, get told within the bounds of this diary. (The Essex lady love in question is likely Jessie Ferguson, whom Atkinson would marry in 1915.)

After Atkinson returned to London from his jaunt, he and Pennell (along with their roommate Jimmy Wyatt) took the Scottish Express as planned. At the estate, called Eden, they met Cherry who was already there, as well as Atkinson’s aunt, the recently widowed Lady Nicholson. Other guests joined in the holiday including Mrs. Wilson, and the party enjoyed motor trips to local landmarks, parlor games, and partridge shooting: “We were out after Partridge & got 6 ½ brace & 3 hare (my shooting worse even that usual) & we had a jolly day. Jane is a very safe shot missing very few.”

Cherry departed on September 24th but Atkinson and Pennell (and their roommate Wyatt) stayed until October 1st: “My shooting improved a bit under Jane’s coaching which was very satisfactory.”

After returning from Eden, Cherry invited Pennell to Lamer again, where “[there] was only Cherry & myself, a singularly thoughtful idea of his.” I think it’s quite possible they discussed what must have been a deeply wrenching emotional situation for Pennell, knowing that there was nothing he could do about Atkinson’s attachment to Jessie other than be happy for his dear friend.

It’s surely not coincidental that less than a month later, in early November 1913, Pennell visited Oddington again and proposed to Katie Hodson in a scene he describes as having “dropped a bombshell in the vicarage.”

Katie had been mentioned in the diary before in passing—as Gerry’s only sister, Pennell had known her family for a decade and watched her grow up. But no romantic inclination was hinted at, at least not in the volume of the diary in question, and certainly not to Katie herself, for from the way Pennell describes it, she was totally blindsided: “I know the poor girl had no idea either way but saw no other way to make her think of me. Mr. & Mrs. Hodson & all the family are delighted, the dear old woman is delighted all except poor Katie who is having rather a bad time.”

She didn’t accept him right away. The family left for a six-month stay in Switzerland a few days later, and he had to wait for a letter from her saying yes or no.

In the meantime, he returned to London. First order of business: seeing “The Great Adventure” again and having dinner and a “tête à tête” with Atkinson at Les Gobelins restaurant, which included discussion of a possible future Antarctic expedition.

On November 27th, “Katie’s letter came accepting me, which only needed a telegram to make us engaged. Dear little girl I am afraid it is a bigger step for her than for a man.” Pennell described his discomfort at the letters of congratulation that then poured in: “It is very complimentary but far beyond that makes one almost feel a cur.”

December found him almost done completing all his Expedition work, seeing “The Great Adventure” yet again and having a celebratory engagement dinner with Atkinson and Wyatt. After the New Year he recorded turning over his magnetic work to Dr. Charles Chree, superintendent of Kew Observatory, and on the first weekend of 1914 saw Peter Pan with Atkinson and a visiting Lillie, describing the play as “delightful, a real living masterpiece” and Lillie as “very flourishing.” On the night before he left for Lausanne, Pennell dined with Atkinson at Simpson’s.

Pennell enjoyed Switzerland, commenting on the “Cleanliness, Good quality of shops & moderation in prices, Politeness & good humor of the shop attendants without servility” of Lausanne. He and the Hodsons skated, skied, attended concerts, and drank cafe au lait.

Saturday the 24th of January was Katie’s brother Charlie’s last day on the trip. Pennell wrote, quite revealingly, about the experience of being alone with her.

“After Charlie left Katie being thrown entirely with me without brotherly support felt I think less doubting & happier in her mind. Poor little girl she gets a good deal of heartache these days & is full of doubts & perplexities. Now it seems as if she had got over her sort of fear of me & only has to overcome her feeling of shrinkage at the thought of marriage – from its physical side. Brought up in complete ignorance of natural functions as K. & so many others are this idea of copulation when first presented to a girl’s mind must indeed be frightening.”

After returning to London on the 27th, Pennell resumed work, dinners and theater, including a dinner with Atkinson and his aunt Lady Nicholson, and seeing “The Great Adventure” for the FOURTH time, with Lillie.

Pennell spent some time with Atkinson at the London School of Tropical Medicine, where Atkinson was working, keeping him company and assisting him where he could.

In a parallel to the above note about Katie’s ignorance of sex, Pennell wrote that “Jane has been splendid explaining aspects of the physical side of marriage. He is a friend such as most men never find, & in this very personal & in many ways strange problem he answers questions that if father was alive I should find out from him.”

😳!

By this point, future plans were in place for both of them. Atkinson was going to go with Cherry to China on an expedition led by parasitologist Dr. Robert Leiper to investigate a schistosomiasis outbreak there; Pennell had been appointed to the HMS Duke of Edinburgh.

He went on a farewell tour, visiting “the Cambridge pack” of Debenham, Priestley, and Wright; seeing his sister Winifred off to her new missionary post in Africa; hunting with the Avon Vale Hunt; seeing “The Great Adventure” AGAIN (the fifth time) with Atkinson and Rennick; and moving his things out of the house on Queen Anne Street.

“It has been the making (to me) of the last 9 months, having Wyatts house to live in with Jane under the same roof,” Pennell wrote.

Afterwards

The diary more or less ends there—with war looming in the offing.

Pennell and Katie married on April 13, 1915; shortly after, her brother died at Ypres, and then her father passed away. A little over a year after their marriage, Harry Pennell died tragically aboard the HMS Queen Mary in the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Katie did not remarry until 1945.

Atkinson married Jessie Ferguson on August 12, 1915 in Essex. He came near death after the explosion aboard HMS Glatton in Dover Harbor in 1918, losing an eye and being severely burned. His wife passed away from cancer ten years later; he remarried quickly to her cousin, but died himself mere months later in early 1929. Neither Pennell nor Atkinson had children.

Lillie, the eccentric biologist who shared a fondness for Atkinson with Pennell, worked as a military bacteriologist, but by the end of the war had been institutionalized due to a nervous breakdown (he remained institutionalized until his death in 1963). Cherry-Garrard commanded a squadron of armored cars on the front but was invalided out due to depression and illness, and spent the remainder of the war and the immediate aftermath working on The Worst Journey In The World, published in 1922.

The full story of the ex-Antarctics in World War I is told in Anne Strathie’s From Ice Floes To Battlefields, published in 2015. It was originally conceived as a Pennell biography and thus relies heavily on Pennell’s diaries, but overall is a detailed and very well-researched narrative of the post-expedition lives of Scott’s men.

In fact, if I had read the book before I came across the scanned diary marked “PRIVATE,” I would not have felt compelled to read the whole document, because the book seems to cover all the bases, with plenty of excerpts detailing Pennell’s experiences.

But when one reads the diary first, and then the book, it is immediately apparent that Pennell’s feelings towards Atkinson have been elided. No mention is made of either of the two explicit “in love” quotes, nor even of the emotional tenor of the other consistent and frequent mentions of Atkinson which go above and beyond how Pennell refers to any of his other friends. To say nothing of his wife! (It does include a brief reference to Pennell resorting to asking Atkinson about the “physical” side of marriage, however.)

I won’t claim to know why this omission occurred, only that I think it’s important that it is corrected now.

Harry Pennell was an energetic, hard-working, cheerful, intelligent man with an abiding love for the natural world around him and for taking pleasure where he could find it. He was adored by his shipmates and they grieved him intensely when he died, especially Cherry who according to his biographer Sara Wheeler “admired [him] tremendously.” In a section cut from the final version of Worst Journey, Cherry eulogized Pennell thusly:

“In Pennell’s heaven they will work thirty hours in the day . . . He will perhaps keep the Celestial Log Book, and the record of the animals sighted . . . And every now and then he would ask for leave to go and take some of his friends in Hell out for dinner. I hope he will ask me.”

Based on the personality that shines so clearly through his private writings, it seems highly unlikely that the conscientious, dutiful Edwardian Pennell ever confessed the true depths of his “violent” feelings directly to Atkinson—although Cherry and Lillie might well have known, if only through observation. It’s also unclear whether Pennell conceived of his affection as having a sexual or physical component: if he did, given his candor in other matters, he may have remarked on it, but that aspect is conspicuously absent.

In a letter to Cherry-Garrard immediately following Pennell’s death, as quoted by Strathie, Atkinson writes “Penelope has gone and I am very sore at his loss as I know you will be too.” Sarah Airriess notes in her post about Pennell that “[Pennell’s] glowing record in Atkinson’s narrative has gone unpublished.”

I’d very much like to do more research to uncover Atkinson’s side of the story, and look forward to taking a look at his letters at the SPRI, but for now I would just like more people to know of the glorious summer in London, before the war, that Harry Pennell spent “absurdly in love” with him.

Edit, November 2023: If you’d like to read on about Atkinson and Pennell, including Atkinson’s side of the story, please check out my follow-up post!

Huge huge thanks to the Penelopatchicus Project transcribers & proofreaders: Sabina, Eva, Han, Newt, Glimpses, Ireny, Anna, Jess, Rebecca, Sarah, R, & Spencer. & Vini for Gerry research!

Further reading:

Strathie, Anne. From Ice Floes to Battlefields: Scott’s ‘Antarctics’ in the First World War. The History Press, 2016.

Wheeler, Sara. Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard. Random House, 2002.

Leave a Reply to admin Cancel reply